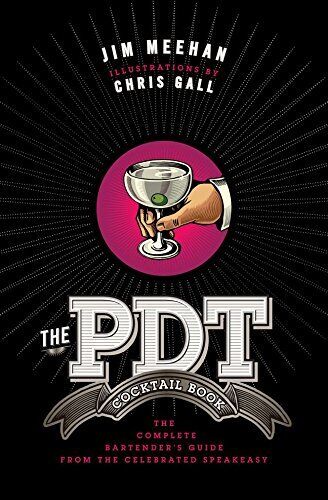

I need to remind you again that the title of this cycle of reviews is a paraphrase of the unforgettable book by Ladislav Mnacko, “Delayed Reports”. Why do I need to do that? Because this time, we’re reviewing a quite recent publication. Jim Meehan, known to many readers as a bartender at Pegu Club and later co-founder of PDT (Please Don’t Tell), contributor to Mr. Boston Official Bartender’s Guide, and now the owner of the consulting firm Mixography, Inc., based in Portland, Oregon, released this book at the end of last year as his second book after The PDT Cocktail Book.

Let me say right from the start that Meehan’s work aims to become a beacon in the bartending industry in the early 21st century, standing beside Embury’s “The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks,” which we acknowledge as holding that position in the previous century, and to some extent, alongside DeGroff’s “The Craft of the Cocktail.” In a certain sense, however, it surpasses these and several other frequently cited works. The surpassing factor comes from Jim’s decade-long practice, which wouldn’t be that much on its own, but especially from his analytical thinking applied to our craft.

Traditional Formula, Yet…

The book’s structure and chapter arrangement already signal that the author hasn’t entirely avoided the traditional formula but has supplemented it with unconventional items or at the very least processed traditional items in an unconventional way. For instance, he names the connoisseurship part “Distillery Tour,” and indeed, he manages to evoke the feeling of a tour through a distillery. In the chapter “Spirits & Cocktails,” he uses an arrangement of recipes by base, a format as useful as it is less common (finally, someone noticed that bases can also be Liqueurs or Aperitifs, which he includes such as Vermouth, Quinquinas, Bitters, Absinthe Blanche and Verte, Sparkling Wine, Fortified Wines, and even Beer and Cider). He acknowledges the importance of a Cocktail Menu, focuses on service theory, and hospitality.

History

Scores of authors before Meehan have covered the history of cocktail culture with varying degrees of success. What did he contribute to it? Primarily, he emphasized some moments that we tend to overlook or simply aren’t aware of, reminding us of the connections that triggered or enabled them. It was only within the pages of this book that I discovered the existence of the former Tudor Ice Company, which supplied bartenders with ice at the end of the 19th century and allowed them to bring the cocktail temperature close to 0°C. He documents that the term “mixologist” isn’t a concept born in the last ten or twenty years (he notes its appearance in 1856), emphasizes the significance of immigrants who shaped the American bar scene at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, and bravely reminds us that the so-called Golden Age of Cocktails, partly caused by Prohibition from 1920 to 1933, was also a period of corruption and dangerously reckless drinking.

I must admit that I never realized that Charles H. Baker and H. L. Mencken weren’t bartenders but journalists, just as much as the distant origins of the practice, where producers organized bartender competitions and released new recipes primarily to promote their products, not for the development of the bar scene. For the insight about the infiltration of the electric mixer into bartender equipment, leading to the widely accepted belief that a true Daiquiri should have the consistency of sorbet, he deserves top marks! Connecting the decline in cocktail quality in the sixties and seventies with the trauma caused by the Vietnam War and the tumult around Nixon’s administration requires precisely the kind of thinking I mentioned earlier. The most optimistic part of the chapter is then “The Craft Cocktail Revival.” Here, names like Audrey Saunders, Sasha Petraske, Dushan Zaric, Dale DeGroff, and others shine, to put it in the words of a movie’s final credits. Closing this part of the book with enthusiastic words about the present – “There’s never been a better time to be a bartender” – is fitting.

Jim Meehan’s Practices

The strongest points of Meehan’s work are his practical guides, notes, and attention to the details of a bartender’s practice. For instance, he reminds us of the risk of admitting a group larger than eight into a bar because the bartender simply can’t handle it with the required quality. How differently modern Central European managers calculate, driven by the necessity of profit. Who realizes that not only lime juice turns bitter within thirty minutes, but even fresh fruit juices lose their freshness after eight hours? Who pays attention to the origin of sugar for making sugar syrup? Or even its grind size? How many bars serve fixed portions of a cocktail in overly large glasses, drowning not only the drink but also the willingness of a guest to pay what seems like a high amount? And have you thought about whether it’s better to provide bartenders with working tools or to have them use their own?

And here are two golden insights that I would display in every bar’s dressing room and backstage area: Ostentatiously tasting every prepared cocktail is nonsense when, in one evening, I mix the twentieth, thirtieth Martini. What’s the risk here that the thirty-first Martini will taste different if the bartender followed the same process? And is it really necessary for every cocktail to be ice-cold when it’s clear that excessive cooling ruins the taste? And what about double straining? Have you considered what it does to an aerated cocktail after vigorous shaking? And does it make sense to serve a Margarita on the rocks? Meehan’s manual addresses these and dozens of other phenomena in a bartender’s practice with informed comments.

100 Recipes

The hundred recipes contained in the book encompass both notoriously known titles and instructions for cocktails that Jim evidently favors. In any case, they’re all accompanied by excellent photographs, and gentlemen modern bartenders, they’re not in any way similar to salads or fruit compotes. Their design stands out with simplicity, elegance, and speaks of the taste of the one who mixed them.

Each recipe is divided into three sections. Origin presents documented history. Logic develops a view of the drink and its evolution in terms of place. Hacks offer a guide on how to substitute unavailable ingredients with similar ones or twist the recipe. The only inconsistency here is the specific brand mention of individual ingredients. Since the author doesn’t favor just one of them, he can hardly be accused of being dependent on specific products. The combinations seem credible, but for a reader who wants to play the recipes by the notes, sometimes acquiring the prescribed tones may be difficult.

Cocktail Menu & Service

The conclusion of the publication consists of a managerial recipe book covering topics like creating a bar menu – here, Meehan expertly comments not only on the content but also the form, right down to details like printing processing – describing how one can formulate those signature cocktails and how to help them become global stars like the Penicillin. (Jim, thanks for knocking the sycophantic name Porn Star Martini; I wouldn’t dip a toe into this cocktail just for its lascivious name.)

Meehan’s Bartender Manual boasts several other useful features. Since every author has their favorite titles that others may not, an extensive bibliography of professional literature presents an opportunity to expand one’s own list of books that might never come into our hands – bartenders must not only read but also practice – but it’s reassuring at least to know that they exist.

What to say in conclusion? I won’t describe how I got my hands on the manual. I got a bit frantic and paid sinful money for it. If you go about it smarter than I did, you can get the book for around 20 to 30 pounds. It would be worth not just reading but carefully studying, even if it cost you ten times as much.